Americans love war

October 21st, 2012

Probably so does the rest of humanity.

Here in the USA, we have:

- The War on Cancer

- The War on Drugs

- The War on Poverty

- The War on Drunk Driving

- Hoover’s “War on Crime”

- Jimmy Carter said the 1970s energy crisis was “the moral equivalent of war”

Then we have the “Good War”, war movies (good guys vs. bad guys), war heroes, and countless war metaphors.

All these wars are supposed to be good things. Necessary things.

Whatever else he was, Jimmy Carter didn’t seem like a nasty guy. But think about “the moral equivalent of war”. Was Carter saying that he thought it was OK to lie in order to deal with the energy crisis? To cheat? Steal? Kill?

Cheating, lying, destruction, theft, and murder are all allowed (indeed, acclaimed) in war.

So is groupism that would otherwise be criminal – in war, when the enemy leaders attack you, it’s OK to respond by killing innocent civilians – so long as they’re subjects of your enemy. Or, even, just in the way.

We declare war on whatever we don’t like because, in war, the normal rules of civilized society don’t apply. And people, especially people in power, don’t like to be constrained by the rules of civilized behavior.

The universe is not parsimonius

October 21st, 2012

One of the defining characteristics of the universe is that it is not parsimonious.

Consider that fish produce many thousands of offspring to replace themselves once – all but two don’t make it to reproduction.

Consider evolution.

Consider the proportion of the Earth’s mass that participates in the biosphere. Of the solar system’s mass. Of the galaxy’s mass.

Consider the number of planets in the universe, and the number that have people on them (~ one).

Consider the proportion of the universe’s mass that is even matter. And the proportion of matter that has an atomic number greater than two.

Now consider the Many Worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics.

The universe is not parsimonious.

[This is not to disparage Occam’s Razor. Parsimony in explanation is indispensable. But the thing being explained need not itself be parsimonious.]

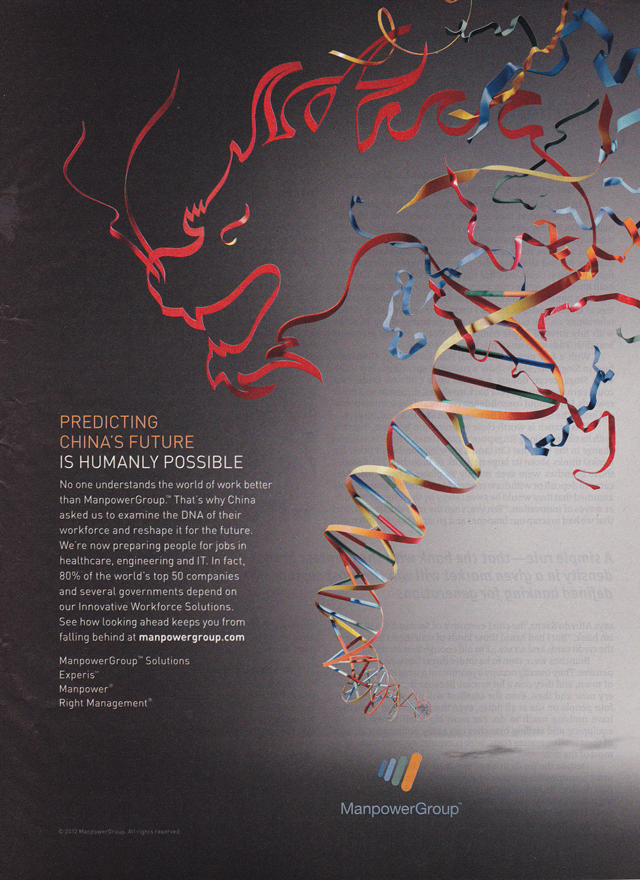

Reshaping DNA

May 30th, 2012

Why school reform never works

March 4th, 2012

Annie Keegan has a posting on open.salon.com about textbook quality that has been getting a lot of attention lately. It’s worth a quick read.

She bemoans the quality of (US) K-8 math textbooks, and blames it on rushed and underfunded development schedules caused by the greed of a quasi-monopoly of “educational publishers left after rabid buyouts and mergers in the 90s”, plus squeezed budgets.

Of course this is true in a trivial sense – the textbooks are in fact horrible, publishers do try to maximize profits, budgets are always less than one would wish, and the textbooks are indeed “there’s no other way to put it—crap”[1].

But she completely misunderstands the causes. And this misunderstanding is likely to lead to more of the same problems, instead of solutions.

Keegan writes:

At one time, a writer in this industry could write a book and receive roughly 6% royalties on sales. The salesperson who sold the product, however, earned (and still does) a commission upwards of 17% on the same product. This sort of pay structure never made sense to me; without the product, there’d be nothing to sell, after all. But this disparity serves to illustrate the thinking that has been entrenched industry-wide for decades—that sales and marketing is more valuable than product.

First, the 6% royalty on all sales of the book is not comparable to the 17% commission on an individual sale to a single school. The salesperson only earns commission on what she sells. There are many salespeople who split that 17% of the book’s total sales, but only one author who collects all of the royalties.

And I don’t think Keegan would complain that a bookshop earning a 40% markup on a book is an indication that retailing is somehow more important than authorship.

Second, the “the thinking that has been entrenched industry-wide” does not decide how “valuable” each contribution to making a book is. There could never be any consensus on that.

Instead, compensation is based on supply and demand – if more people want to be textbook authors, that increases the supply and reduces the pay. If less people want to sell them, that decreases the supply and increases the value of salespeople. If Ms. Keegan thinks salespeople have a better deal, perhaps she should become one – this is how the market shifts labor (and other resources) from less-valuable to more-valuable purposes. If she prefers to remain an author despite the (supposedly) lower pay, that’s her choice, and that choice shows that, to her, being an author (with lower pay) is better than being a book salesperson (with higher pay). She ought not to complain if she is better off — by her own standards.

But none of these misunderstandings get to the heart of why the books are “crap”.

The books are not crap because of the publisher’s greed and the limited budgets.

People who make televisions and plumbing supplies and instant noodles are greedy humans, too. And the people who buy them always wish they had more money to spend than they do. Yet these things aren’t crap.

School textbooks are crap because, unlike televisions and plumbing supplies and instant noodles, the people who make the decision to buy them (administrators and school boards) are not the same people who use them (students and parents).

These two groups of people – buyers and users – have different priorities. The quality of content is foremost for the users of the textbook, but the buyers are easily influenced by other things – fun trips to “educational seminars”, fancy lunches paid by salespeople, kickbacks of varying forms and legality, etc.

In the end, publishers must supply what buyers want, or face being replaced by other publishers who will. What students and parents want is relevant only insofar as it influences what buyers want. Even if a publisher were to have high standards, ensure adequate budgets and schedules, etc. to produce a high-quality product, this would only mean that their expenses would be higher than those of publishers who concentrate only on what sells books.

This problem cannot be solved by changing how publishers work or how school boards and administrators buy textbooks. Buyers will always do what is good for buyers and sellers (publishers) will always do what is good for sellers – increasing budgets simply means they will do more of it. This is an iron law of nature.

The only solution is to make the buyers care more about the wishes of the users – parents and students. As long as students are assigned to schools without choice, administrators have little reason to fear losing students and the funding the comes with them – it’s easy to prioritize (and rationalize) their personal interests as buyers over the interests of users. School choice forces administrators to care about losing dissatisfied students and parents – and so to demand quality textbooks.

Like pushing on a string, changing what suppliers offer does not change what buyers want. Buyers will simply find other suppliers with less scruples. You can only pull on a string – change will happen only when buyers demand better quality from publishers, and that can happen only when buyers and users have the same interest – quality textbooks and quality education.

————-

[1] Of course the whole issue with math textbooks is moot because math doesn’t change; there’s no reason to update math textbooks in the first place. If you’re a school, my advice is to find a good math textbook that’s 100+ years old (and therefore out of copyright) and use it.

But book salespeople won’t take you on fun trips if you do that, so while this advice is best for your students, it might not be best for you as an administrator. Which is my larger point.

(Some will say that math doesn’t change but teaching methods do – I agree, but for the very same reasons that textbooks are “crap”, they don’t change for the better.)

A Day in the Future

May 19th, 2011

(This was originally posted 2011-01 on Raptitude.com by David Cain. Reposted here by permission.)

I awake in bed. I’m warm and safe, like every morning. Outside it is twenty below zero, but from inside my home winter seems far away.

As I rise and stretch, I notice I’m sore. Not from tending the fields though. I have no fields. Some unseen person does all the field-tending for me. Sometimes I forget that there’s any field-tending going on at all.

I buy all my food — I wouldn’t know how to grow it or hunt it. Three or four hours’ pay gets me a week’s worth. It’s a pretty good arrangement. I’m thirty years old and I’ve never gone a day without food.

My soreness is actually from my leisure time, not work. I spent yesterday sliding down a snow-covered slope with a board attached to my feet. After that I was pretty worn out, so I went to a friend’s house, drank beer that was wheeled in from Mexico by another person I never met, and watched a sporting event as it unfolded in Philadelphia.

I don’t live in Philadelphia, but my friend has a machine that lets us see what’s happening there. I have one too. Almost everyone does.

The sun won’t rise for another hour, but I don’t need to light a fire or candles. I have artificial ones, mounted on the ceiling. Hit a tiny switch and I can see everything, any time of day.

I bathe while standing. The water comes out whatever temperature I like.

I use a few machines in my kitchen to get my breakfast ready. It takes about five minutes. Toasted buckwheat groats with raisins, almonds, dates and sunflower seeds. I don’t know where it came from but I’d be surprised if it was from anywhere near here.

As I eat, it occurs to me that my co-worker has a machine I might need to use at work today, so I want to make sure he brings it with him. We work about ten miles from my home, and he lives about ten miles from me, but that’s no problem. I’ve got a device that lets him hear my voice from that distance. Wherever he is, I can talk to him.

One minute later I’ve solved that problem, and forgotten about it.

I put my dishes into another machine, which will clean them for me while I’m away at work.

I get dressed and leave. My destination is ten miles in the distance and I’ve got twenty-five minutes, which is plenty of time, because I won’t be walking.

I get into my most expensive machine. It’s actually quite miraculous, but I forget that all the time. It allows me to sit in a comfortable chair, sealed from the elements, while it propels me at incredible speeds.

Just like my home, I can make it any temperature I wish inside. I don’t have to exert any real effort to make the thing go. I use my hands and my toes to control it.

I don’t know quite how it works, but it’s powered by a liquid I can buy pretty much anywhere. For two hours’ pay I can buy enough of it to transport myself hundreds of miles from here. I can transport hundreds of pounds of whatever I want, and even listen to long-dead musicians singing and playing instruments while I do it. I remain sitting comfortably the whole time.

So I hurtle myself to my workplace, which is well beyond the horizon, looking from my house. There, I do what a corporation asks me to, for most of my daylight hours. It’s not that tough really.

I hurtle home in the same manner, without really thinking about it. I make dinner for myself, and eat. Then I turn on one of my favorite machines. It’s about the size of a book.

It has a glowing window inside it. A single page. But I only need one page because its contents change at my command. Sometimes there are words, sometimes photographs, sometimes both. The photographs can move and talk.

The stuff in the book can be written by anyone in the world, even as I’m reading it. There’s more in that book than I could ever read. It provides me with unbelievable advantages. Anything I don’t know, I can find out in a few seconds.

I can get instructions on how to do pretty much anything that has ever been done. I can summon complete histories of almost any person or culture you could name, expert opinions on anything at all, unlimited advice, unlimited entertainment, unlimited information. I can buy pretty much anything from where I’m sitting, and have it brought to my door.

I can even write anything I want and publish it myself. I don’t need permission or credentials. The whole world could read it.

These are true superpowers, only we don’t call them that because they’re completely normal. Almost everyone has access to this kind of power. Yet somehow many people complain of boredom, or of not having enough power.

I know it sounds pretty good. Ease and power are everywhere, for almost everyone. But there are downsides.

Because we’re used to ease, we don’t deal with unease particularly well. We are addicted to machines and the powers they provide. Sometimes it’s hard for people to even have lunch without one of them using a machine to talk to somebody who isn’t at the table.

We’ve lost certain skills because machines and cheap services do things we don’t want to do. Some adults don’t know how to cook anything worthy of serving to someone else. Grown men have childlike handwriting. Almost nobody knows how to wait.

We lose track of what’s right beside us, because we can listen and talk across oceans. Some people are barely there because they’re staring at a machine in their hands while they eat, walk down the street, or even while people are sitting right next to them. Even while they’re hurtling down the highway.

We generally don’t fix machines when they break. We buy new ones and have somebody haul the old one off to be buried in the ground. Nobody knows how to fix them anyway.

Because we acquire new possessions so frequently — often without even realizing it — we don’t treat them very well. It’s normal to have boxes and boxes of tools, supplies and ornaments that we don’t use, and may never be used.

We have so many things that they cease to become things. They become indistinct stuff, and their value and usefulness become lost on us. I often marvel at the thought of the unimaginable value someone two hundred years ago could get out of a random box of somebody’s neglected junk.

We forget that what we have is more than what we need. Obscenely more. I know it may sound perverse, but here in the future people often feel like they need more than they have.

***

The sun went down hours ago, but with my artificial light I haven’t noticed. I’ve been up, writing without a pen. When I’m able to summon the willpower, I close my favorite machine and go to bed.

I’m warm and safe, like every night.

Or, you could let the market work

May 18th, 2011

[Hint: You can get around The Economist‘s paywall by linking via Google – just put the URL into Google, then click on Google’s link to the article.]

Last month there was a story about various dirigiste steps the Japanese government might take to deal with the post-tsunami electricity shortage in The Economist (of all places). They published my response in the May 14 issue, again with some unfortunate editing (see “The market for electricity”, halfway down the page). Here is my original version:

Date: Sat, 07 May 2011 19:06:22 -0400

To: letters [at] economist.com

From: Dave <dave [at] mugwumpery.com>

Subject: Or, you could let the market workDear Sir:

I agree with your assessment (“A cloud with a green lining”, 30 April) that Japan’s government has many options to deal with the electricity shortage resulting from the earthquake and tsunami. As you say, they could encourage solar power, subsidize LED lighting, push for batteries to shift demand away from peaks, etc.

Alternatively, they could do nothing at all, and allow electricity users to bid up the price of power until demand drops to meet the limited supply. The resulting high price would by itself encourage alternate sources of supply and force conservation without any need for “publicity” or nagging. More, it would encourage people to find clever ways to increase supply and reduce demand that the mandarins in Tokyo might never have thought of.

And all without costing taxpayers a penny, or feeding subsidies to the politically-connected.

The sad thing here (on top of the greater tragedy of the earthquake itself) is the lost opportunity for entrepreneurs to come up with efficient and innovative solutions to address the electricity situation.

But the market works even when governments attempt to suppress it – just less efficiently. If the Japanese government decides to dole out subsidies and propaganda instead of letting the electricity price rise, that won’t end the shortage. Rolling blackouts will still cause electricity consumers to increase their own electricity supplies, and adapt their demand to the blackouts, by buying their own generators, investing in battery storage to supply power during down-times, etc. But there will be a lot less incentive to cut consumption, since cheap power will still be available in bursts.

Eventually the Japanese electric grid will be rebuilt to handle the demand, but in the meantime adaptation will be slower, and the pain more prolonged, than it would be had the authorities let the market do its thing. But despite the best efforts of the government, electricity users will adjust and find ways to get by with the limited supply. And that is the market in action.

Copying is not theft

February 24th, 2011

Another letter to the Economist:

Date: Thu, 24 Feb 2011 09:06:36 -0600

To: letters [at] economist.com

From: Dave <dave [at] mugwumpery.com>Subject: Re “Ending the open season on artists”, 19 February

Dear Sir,

As a an “aghast” digital libertarian, I object to your presumption that stronger copyright enforcement is good or necessary for artists.

No one disputes that artists must be rewarded for successful creation. (Middlemen are another story.) Copyright was a reasonably effective system when copying was expensive anyway and the means of reproduction were relatively centralized publishers and distributors, easily policed. Now that works can be copied costlessly by any individual, the principle of limiting copying is both unworkable and inappropriate, as copying (although illegal) is not theft – because copying does not deprive the original owner of anything.

Certainly, artists must eat. The challenge is to find new business and legal models to accomplish that without needlessly depriving the public of the full enjoyment of the fruits of creation.

Attempts to perpetuate obsolete business models by law are not the solution.

It is hard to make a strong argument in a letter short enough to get published.

My larger point is that there is what economists call a “deadweight loss” when someone who would have enjoyed a creative work doesn’t because of costs imposed by copyright.

Say we’re talking about a copy of The Beatles “A Hard Day’s Night” (which, completely off-topic, has some of the lamest lyrics imaginable – “…to get you money to buy you things“??).

Some consumers are willing to pay the asking price for the song under the copyright system. In that case the artists get 10 or 20%, and the middlemen get the rest. (And yes, the studio technicians, etc. need to get paid too, but not necessarily by a record company – painters seem quite able to buy blank canvas without middlemen to help.)

But more consumers (usually far more) are not willing to pay that much. They’d enjoy having a copy of the song, but not enough to justify the price. These people are going to be in the majority almost regardless of the price asked. This is the deadweight loss; value that could have been realized without cost to anyone, but wasn’t.

To make it clearer – imagine we’re talking about a $1000 copy of Adobe Photoshop instead. How many of the people who would benefit from using it are willing to pay that much? Very few. Yet it would cost Adobe nothing at all to let them use it for free – if that didn’t discourage those few who would pay from doing so.

Of course, under the copyright system this loss is necessary to make the system work – otherwise no one at all would pay. And this is precicely the problem with the copyright system – it necessitates the deadweight loss to work.

As I implied in the letter, this wasn’t such a terrible flaw when copying was expensive anyway. Records couldn’t be produced for free; paying the artist a royalty only increased the price a little bit, so not much harm was done. But that’s not true in a world where copying is free.

So we need a new system to reward creators for successful creation that other people value. I can imagine a half-dozen ways to do it; so can you. It will take some experimentation and evolution to get there, but propping up the obsolete copyright system is not going make it come sooner.

AT&T’s roaming fees and the American Way

August 23rd, 2010

Last week I came back from a brief visit to Croatia (visiting family).

I took along my trusty iPhone, having first jailbroken and unlocked it, so I wouldn’t get whacked with AT&T’s international data roaming fees.

Over the course of 10 days, I used 44 Mbytes of data; I consider that quite moderate – a little Web browsing, minimal email, and some Google Maps. (I’d expected to use about 10x as much.)

I bought a SIM card from one of the local networks, VIP (a Vodafone affiliate, I think).

VIP’s deal was as follows: For HRK 100 (US $17.40 at today’s exchange rate), you get a prepaid SIM card loaded with HRK 100 of credit. Calls come out of that at $0.14 to $0.44/minute, depending on time of day and what network you’re calling (landlines are less). International calls are $0.47 to $1.08/minute, depending on where you’re calling (calling the US is the $1.08/min rate).

Again out of your HRK 100 credit, you can buy data service – 20 MBytes for HRK 15 ($2.61) or 100 MB for HRK 30 ($5.23). (Don’t believe me? Look here. ) I went for the 100 MByte deal, using up HRK 30 of my HRK 100 credit. Since I only used 44 MBytes of that, the rest went to waste. I don’t really know how much credit was left when I came back to the US; but I know I was able use voice and data both in the Munich airport and in the USA using the same card.

So, 10 days’ use of the iPhone, voice and data, cost me $17.40. And I didn’t use it all up. (Service was great, by the way – much better 3G data coverage in rural areas than I get in the USA.)

Just for curiosity, I checked how much AT&T would have charged me for the same thing.

Their standard international data roaming rate is quoted as $0.0195/kByte. That’s just shy of 2 US cents per 1024 bytes, or $20/MByte. I used 44 MBytes so that would have been $879. Yes, nearly nine hundred dollars. For very light usage; I could easily have used many times more if I’d been traveling for business.

But, of course, AT&T says if you’re going to be travelling internationally, you really ought to buy one of their “Data Global” packages – 20 MB for $25/month, 50 MB for $60/month, and $120 for 100 MB. (Recall that I bought 100 MB from VIP for $5.23.) And if you go over your monthly allowance, it’s $10/MB.

What is AT&T thinking?

Google on “iPhone international data roaming” and you’ll find lots of horror stories about multi-thousand-dollar AT&T bills from short trips. I didn’t get whacked, but what does AT&T think is going to happen when someone gets a $3000 bill after two weeks in London, or a $60,000 bill after downloading one episode of “Prison Break”? They might or might not get paid, but for sure they are going to lose a customer – forever. Each and every time they send out a bill like that.

It may be legal, but it is bad business – incredibly bad business.

One of the things that has made the US such a wealthy country is a business culture that includes the idea of a “fair price”. Although it’s generally legal to charge any price the market will bear – even taking advantage of buyer ignorance or desperation – mainstream American culture supports the notion that there is a “fair price” – the price that an informed buyer would pay in a competitive market, considering circumstances of location, quality, convenience, etc.

So, for example, Americans frown upon selling generators for $10,000 during a blackout, if they go for $1000 at normal times. Or the rural tow truck driver who wants $2000, cash, to pull your car out of the muck, just because the next closest tow truck is hours away.

Many economists wouldn’t have a problem with that – in a certain narrow sense, those kinds of price spikes (“gouging”, if you like) may be efficient. But a society in which most sellers feel revulsion toward “taking advantage” is one in which buyers are more willing to engage in transactions. If buyers feel they’re unlikely to get screwed because of their ignorance (as in the the case of AT&T here) or desperate circumstances, then there is more commerce and less effort expended in investigation of deals and precaution against getting caught by local monopolists. In short, transaction costs are lower for everyone.

I’m not advocating legislation here. But the American attitude has it merits. And AT&T is not making itself any friends or building any customer loyalty.

What is this strange feeling?

August 11th, 2010

It’s the sunburn. It’ll go away in a few days. Probably.

The Toyota Witch Trials

March 10th, 2010

No one else seems to be saying it, so I will.

The hysteria about run-away Toyotas is driven by a xenophobic witch hunt.

There is nothing wrong with Toyota vehicles. They do not accelerate uncontrollably. Ever. There’s nothing wrong with the floor mats, electronics, etc. Claims to the contrary are lies.

I’m not going to focus on the engineering reasons why such claims are utterly unbelievable – the chance that the accelerator, brake, gearshift, and ignition all fail simultaneously in a way that allows acceleration and nothing else, then miraculously correct themselves afterward so that there is no sign of any flaw – is as close to zero as anything gets in this world.

It is interesting that Toyota is having these “problems” only in the United States. Not in Japan, China, or Thailand. Not in Australia or New Zealand. Not in the UK, not in Sweden, not in Spain, Germany, Russia, or Romania. Not in Nigeria, South Africa, Botswana, Uganda. Not in Canada. Just in the USA. Even though they sell the same cars in all these places.

And that all the publicity about deadly flaws in Toyota vehicles started in 2009, just after headlines like these:

Toyota Passes General Motors As World’s Largest Carmaker (Washington Post, January 21, 2009)

Toyota Ahead of G.M. in 2008 Sales (New York Times, January 22, 2009)

Toyota now the largest motor-car manufacturer of the world (BusinessWeek, April 11 2009)

I know what you’re thinking. Surely all the claims of malfunctioning cars, actual crashes, etc. can’t be simply made up by jingoistic Americans annoyed that the national champion has been bested by the yellow devils.

No. That’s not what I’m claiming.

There are something like 300 million cars in the USA. If each one is driven once a day, that’s 110 billion trips each year.

When a driver starts a car, there is some small but finite chance she’ll step on the gas by mistake when aiming for the brake. It’s happened to me, and to most people I’ve asked. Most of the time we notice and think “oops – wrong pedal”, and that’s the end of it.

But sometimes, rarely, people don’t notice. Instead they panic. They press harder on the gas, instead of pressing on the brake. They think they’re already pressing on the brake, and the car is going too fast. So they press harder. On the gas.

This doesn’t happen very often. But 110 billion trips/year. Maybe 20% of them in Toyotas. It does happen sometimes.

If the driver is on a highway, usually even if this happens the driver will think to turn off the ignition. Or put the car in neutral. But not always. Some people are just panicky and don’t think clearly in emergencies. Some are bad drivers. And even good drivers can have a bad day.

Eventually, one of two things happens – the car hits something or the driver figures out what happened and lets go of the gas. If there is a crash, the driver may very well believe afterward, in all honesty, that there was something wrong with the car. If there wasn’t an accident, the driver may have made a fool of themselves, caused someone else to have an accident, or got caught speeding. Most people are honest, and will admit they made a simple mistake. But 110 billion trips/year. Not everyone is honest.

This is exactly what happened with Audi in the early 1980s – a few reports made the media and confused or dishonest people suddenly had an excuse to blame someone else for their accidents. Or to sue for damages. There was nothing wrong with Audi’s cars, other than having the gas and brake pedals a little closer together than some drivers were used to. But sensation and terror sells advertising, and most people are stupid enough to believe everything they see in the media.

So – a few Toyota drivers make this kind of mistake, and blame it on the car (mostly in honest confusion). Happens all the time, to all makes and models of car.

But – Toyota Passes General Motors As World’s Largest Carmaker !! For the first time in 77 years!

Some in the media, and many in politics, are carrying a chip on the shoulder – America’s champion has been shamed and defeated by the hated Asian devils! So these claims are not ignored. They’re hyped. Toyota is killing people – their cars are deathtraps! Congressmen demand NHTSA investigations. Soon the CEO of Toyota is committing rhetorical hara-kiri in front of Congress and the TV cameras.

Of course, floor mats can get stuck. So can accelerator pedals. It happens to every make and model. But Toyota’s patient explanation that there is no problem doesn’t work. Reason never works when you’re in a witch hunt. So to protect their reputation and avoid even more expensive punishment, Toyota reluctantly negotiates a recall to glue down floor mats and grease accelerator pedals. Under duress – a sort of plea-bargain with the American government (which is unlikely to honor its end of the deal).

The technical term for the whole thing is bullshit.

[In the interest of full disclosure: I am a shareholder of Toyota Motor Corp. Also of Daimler AG and Honda Motor Co., both of which stand to gain sales from this garbage. As well, I own, among other vehicles, a Toyota Prius. Which I am not going to drag to the dealership for a shamanistic rain-dance to make the evil unintended-acceleration spirits go away.]