What would our ancestors think?

May 6th, 2020

Update, June 2020:

After a few months, I’m starting to think my readers don’t “get” what I’m upset about here. So I’ll explain.

The notion that wealthy people, in the name of “fashion”, should dress up to look poor – literally, in clothes falling to rags – is disgusting.

It shows an utter lack of awareness of what poverty is. What hunger is. And the human misery they entail.

These scourges have ravished mankind throughout history. Billions of our fellows lived lives of want, of hunger, of near or actual starvation. As a result they lived with disease, degradation, filth, pain, ignorance, superstition, and fear. This was the common condition of virtually everyone, across the world, for most of history. It was no fun.

It’s not “chic”. It’s not something to be admired or emulated. It’s something to celebrate that we’ve almost eliminated.

My niece, raised in a wealthy suburb of Boston, at age 12 had never heard of the word “famine”, or of the concept. She had no idea what it was, or that such things could exist. It had to be explained to her. Famine – mankind’s oldest enemy.

How is it possible for moderns to be so ignorant of history? Of the state of the world? Of the sources of suffering? Of the realities of nature?

How is it possible to think playacting as a sufferer is “fashion”?

Presumptive insanity

March 17th, 2019

Any adult who actually wants to be President of the United States has something deeply wrong with them, and should be automatically disqualified.

Instead, we should have a system where the citizens elect a small number of representatives, who would meet together and jointly pick someone to do the job.

We could call it an “electoral college”.

On groupism

February 28th, 2019

There’s an old joke (this version is from C. Fink):

A Jewish man and his friend, a Chinese man are sitting at a bar.

The Jewish man turns and punches his friend in the face.

The Chinese man shouts “What was that for?”

The Jewish man replies, “That was for Pearl Harbor.”

The Chinese man says, “I’m Chinese not Japanese!”

The Jewish man replies, “Chinese, Japanese, what’s the difference?”

Then the Chinese man punches the Jewish man in the face.

The Jewish man says “Why did you do that?”

The Chinese man replies “That’s for the Titanic.”

The Jewish man says, “I didn’t sink the Titanic. That was an iceberg!”

The Chinese man smiles and says, “Iceberg, Goldberg, what’s the difference?”

That’s groupism. A random Japanese person is not responsible for Pearl Harbor. That crime was committed a long time ago by other people.

And a random iceberg isn’t responsible for sinking the Titanic. It was another iceberg that did it.

Groupism is blaming innocent people for the crimes of others, because of some irrelevant thing they have in common.

And yet, there are many societies in which collective guilt is a thing – mostly small, primitive societies. Collective guilt has the useful property of making everyone watch one another to prevent crimes – because everyone, including the innocent, will be punished for any crime committed by a single member of the group.

Modern people usually have big problems with that idea, but it has been a successful way of living since ancient times.

I’m one of the people who has a problem with it. My concerns are:

(1) Collective guilt breaks the whole idea of individual freedom and responsibility. In that system, my neighbors get a say on how I live, because they will suffer the consequences of my bad decisions.

But freedom doesn’t mean anything if it doesn’t include the ability to make choices that other people don’t approve of. If you care about individual freedom at all, this is a huge problem.

(2) People usually don’t get to choose which groups they belong to. If I’m born Japanese, and the world treats me as Japanese, and so guilty of the crimes of all other Japanese, I’m screwed – because even if I disagree with and oppose the actions of other Japanese, I still get blamed for what they do.

If people could join and leave groups voluntarily (as with “corporations, associations, colleges, etc.”) then this would be much less of a problem. You’d still have an element of collective responsibility, but people who disagreed with the collective could leave it.

But that’s not how groupism usually works.

(3) Collective guilt societies usually also have collective responsibilities. If I’m born into one, it may be (for example) my duty to obey my elders, to marry only whoever they decide I should marry, to live where they tell me, to do the work that they tell me to, etc., etc. One day, if I live long enough, I may become an elder and get to tell other people what to do.

Basically this means that everyone is a slave of the group. For life. With no way of leaving slavery without breaking the rules of the society.

Again, if you care at all about freedom and think slavery is a bad thing, this is a bad thing.

(This post is adapted from an answer and comments on Quora.com.)

Three things I’ve learned

June 1st, 2018

Important and non-obvious things I’ve learned:

- If you have sufficiently good tactics, you don’t need strategy.

- Sufficiently frequent, deep, and thorough backups compensate for a multitude of sins.

- Everything is more complicated than it seems.

As far as I can tell these things are unrelated. I could be wrong.

Some movie reviews

May 26th, 2018

These are cut-and-pasted from Netflix. With very rare exceptions, I only write reviews for movies I disliked – it’s my way of getting revenge.

There are no spoilers here. All ratings are in the range 1 to 5 stars.

[Edit: I see that 12/14 of the reviews below use the word “stupid”. I suppose that says something not terribly flattering about myself. So be it. It’s still how I feel about these films.]

Things to Come

The Gestapo will save us from war, hatred, and irrationality and create a paradise of identically black-suited heroes who rule and identically white-gowned citizens who obey, all living in a futuristic world with lots of pneumatic tubes. Underground. And they will have television. But, of course the Gestapo (or is it Stasi? Or Checka? hard to tell) rule in the name of Humanity, so it’s all good. But they don’t approve of private airplanes. H.G. Wells personally oversaw every detail of this film. It supposedly represents his vision of an ideal (!) future world. (He supported something he called “liberal fascism”, and it shows.) Acting is high school play quality. (On the low end of that.) Special effects were good for 1938. I give it 2 stars, both for historical interest. The film isn’t worth watching aside from that.

Sunshine

I used to think Gravity was the worst recent science-fiction film. No longer. Gravity was stupid, terrible, and stupid (with great special effects and pretty good acting). But Sunshine is bad on a whole different level. It has *layers* of stupid, each dumber than the next. Layers upon layers of stupid. It’s really an amazing achivement. But not amazing enough to make it worth watching. It’s not “fun stupid” like Plan 9 From Outer Space. It’s just…. well, don’t watch it.

Interstellar

The stupid – it hurts. Physicist Kip Thorne was involved with the scriptwriting. Thanks to him the part about wormholes isn’t stupid. Just the other 99% of the movie is stupid. If you know anything at all about engineering or physics, that is. I won’t give spoilers, but please note it’s difficult to hide the launch of a Saturn V-sized rocket. And the vicinity of black holes tend to have LOTS of x-rays. Not a place you’d want to (or be able to) live. Plus, a little 1930s-style dust bowl is no reason to abandon an entire populated planet. See astronomer Phil Plait’s comments at Slate.

The Man from Earth

Some interest. Others have done it better in written science-fiction. The Mel Brooks/Carl Reiner version (2000 Year Old Man) is much funnier. This movie is all talking-heads (it cost $200,000 to make). And the characters are cardboard cut-outs, very poorly written. But some interesting ideas.

You wrote this on Sat Jan 06 15:36:05 GMT 2018

Mr. Nobody

There’s a solid 25 or 30 minutes of entertainment lurking in this 2 1/2 hour movie. It’s slow. Really slow. The filmmakers even showed they know it – there’s a line in the film “it’s like a French movie – nothing happens”. Synopsis (no spoilers): Choices have consequences. I think most people already knew that, but the film assumes that it’s a mind-blowing concept.

You wrote this on Sun Jul 02 22:27:40 GMT 2017

Argo

Intrinsically an interesting true story, but way too Hollywood for my taste. As others have mentioned, the film inaccurately minimized the Canadian role, and positively insults the heroism of the British and New Zealand embassy staff (for no conceivable reason). Worse for my enjoyment of the film was the obviously made up last-second hitches inserted by the filmmakers. Without spoiling, there are two huge omg-we’re-almost-there-BUT moments, inserted by the filmmakers for suspense. Plus a lot of smaller ones. But this is a true story. These have no basis in history, and are such obvious Hollywood tropes as to break my belief that I was watching something real. It’s like when James Bond defuses the bomb with 1 second left on the clock. You know you’re watching a scriptwriter’s cheap trick, not something that happens in real life.

Gravity

I just watched it. I’m still stunned. Stunned by the utter stupidity of this movie. From the very first minute this movie is idiocy after idiocy. Read the other reviews for some of them, but I could write a book about everything wrong – with physics, with technology, with psychology, with common sense – in this movie. Just in the first 5 minutes (no spoilers): 1) She’s a MEDICAL doctor, yet she’s there to work on an upgrade of the Hubble telescope. Huh? 2) She says she’s nauseous – while in a spacesuit. Does she immediately go inside and take off the suit? Does she have ANY IDEA what will happen if her stomach goes while wearing a space helmet? (Answer: She will choke to death on her own upchuck, while totally blinded as it coats the inside of her helmet.) 3) The stars are visible IN THE DAYTIME. Clooney is DOING CIRCLES (==burning fuel like crazy – he should be out in 90 seconds at that rate) around the shuttle in a jetpack at a speed that would kill him instantly if he hit anything. 4) People describe things being at “7 o’clock” while floating IN OUTER SPACE (so the clock doesn’t even have an up and down, let alone facing in any particular direction) 5) People are asked to “describe their position” while floating in F***ING ORBIT! (What the heck are they supposed to say… “I’m 100 feet south of the tree?!?!?”) 6) She’s a NASA astronaut, but she “crashed” Soyuz in the simulator EVERY TIME. But they still let her fly. And that’s just in the first 5 minutes. It goes on just like that for an hour and a half. My head is still spinning. WHY does Hollywood do this? This movie had a huge budget and A-list stars. How much extra could it POSSIBLY cost to hire a scriptwriter smarter than Bozo the Clown?

You wrote this on Sun Jun 08 03:57:50 GMT 2014

The Hunger Games

Too much killing of innocents. Not enough revolution. “When the people fear their government, there is tyranny; when the government fears the people, there is liberty.” Thomas Jefferson

You wrote this on Sun Nov 25 04:00:40 GMT 2012

Babel

A rather long slow movie about people doing amazingly stupid things and suffering for it. Visually interesting, the characters are hard to sympathize with because they act so stupidly. I found myself feeling they deserved worse than they got.

You wrote this on Wed Feb 15 14:50:33 GMT 2012

3:10 to Yuma

It’s hard to measure these things accurately, but this may be the stupidest movie I’ve ever seen in my life.

You wrote this on Sat Nov 05 10:05:12 GMT 2011

Passenger 57

Too stupid for words. A good choice for MST 3K movie night. Watch for the big fight scene where everyone on the plane needs oxygen masks to stay conscious except, of course, for the guys fighting.

Moon

Stupid movie. First – the premise. An astronaut takes a 3-year stint, all alone, on the far side of the moon mining He-3. 3 years? All alone? Only a crazy person would do that – and it’s hardly a job for crazies. So the premise is unreasonable to start with. Next, part of the plot turns on having no direct communications with Earth, except via relay thru Jupiter (so no real-time comms). Supposedly the comsat is broken. Yet the base is just a short drive from nearside, where the astronaut can easily make phone calls to Earth. Come on – so close to nearside yet there’s no wire to an antenna there? Second, the science/special effects. When he does talk to Earth, there’s no delay. There is low-gravity outside the base, but inside the base it’s just normal Earth 1-G. And bright lights outside give visible beams in the “hazy air”. On the moon? In a vacuum? It was so un-moonlike that, at one point in the movie, the main character is exploring outside the base, and makes a “discovery”. I thought the “discovery” was going to be that HE’S NOT ON THE MOON AT ALL. (But he is; I haven’t spoiled it.) I love good hard SF, and while this film borrows heavily from 2001 and other classics, it is not in that league.

You wrote this on Sun Jun 13 03:01:41 GMT 2010

Iron Man

Stooopid. Plot is weak and very, very predictable. But the “technology” just violates way too many physical laws in far too obvious ways for me to suspend disbelief. And I’m a SF fan! If you liked the comic book, maybe you’ll like this. As an engineer, the whole idea of a “super-suit” just strikes me as ridiculous. Are tanks built in the shape of giant armed men? Hardly. Then there’s the rockets with no need for reaction mass, and people getting smashed into things at hundreds of miles per hour with no injury (suit or not, the human body is only so strong). The special effects were good. And the focus was sharp.

[Added 2018: I liked some of the later ones better.]

You wrote this on Sun May 02 03:00:39 GMT 2010

Spider-Man 3

I liked the first two Spiderman movies. This one was just too stupid to bear, from beginning to end. By halfway into the movie, it had become a MST 3000 session with everyone in my family making jokes about how idiotic this movie was. Even my 6 year old thought it was full of cliches. (He did like it, tho.)

Optimism is a duty

October 26th, 2017

I have never met a philosopher who had anything to say that wasn’t nonsense.

But I have read Karl Popper. He constitutes an existence proof that meaningful philosophy is possible.

The motto Popper seems to have most liked repeating was:

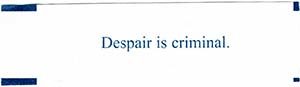

Optimism is a duty. The future is open. It is not predetermined. No one can predict it, except by chance. We all contribute to determining it by what we do. We are all equally responsible for its success.

This appears to be an expansion of Kant’s “optimism is a moral duty”. If I recall correctly, Popper first published this in 1945, in The Open Society and its Enemies.

I’ve used that quote many times, in many places. It summarizes one of my own core moral values. But many people seem to be confused as to what it means.

It seems obvious to me, but Popper found people had the same problem. So he tried to explain.

In a 1992 speech, he said:

The possibilities lying within the future, both good and bad, are boundless. When I say, “Optimism is a duty”, this means not only that the future is open but that we all help to decide it through what we do. We are all jointly responsible for what is to come. So we all have a duty, instead of predicting something bad, to support the things that may lead to a better future.

(Emphasis is mine.)

Two years later, in The Myth of the Framework:

The possibilities that lie in the future are infinite. When I say ‘It is our duty to remain optimists,’ this includes not only the openness of the future but also that which all of us contribute to it by everything we do: we are responsible for what the future holds in store. Thus it is our duty, not to prophesy evil but, rather, to fight for a better world.

Joseph Agassi says Popper’s

… arguments for optimism were diverse. First and foremost, the world is beautiful. (“The propaganda for the myth that we live in an ugly world has succeeded. Open your eyes and see how beautiful the world is, and how lucky we are who are alive!”) Second, recent progress is astonishing, despite the Holocaust and similar profoundly regrettable catastrophes. The clinging to life that victims and survivors of the Holocaust displayed despite all horrors, he observed, stirs just admiration for them that bespeaks strong optimism. Most important, however, is the moral aspect of the matter: we do not know if we can help bring progress and it is incumbent on us to try. This is the imperative version of optimism.

Because the future is undetermined, because it depends on our actions, we – all of us who yet live – have a moral duty to try to make it a good future. And we can do that only with optimism – with the belief that a good future is possible.

The next time you’re tempted to say “everything is going to hell”, “we’re all doomed”, “it’s over now – the enemy has won” …think again.

We always have the opportunity to change things for the better. Nothing is decided in advance – the future is always subject to improvement. And only those with optimism will make the attempt.

Rewards, incentives, and fairness

May 26th, 2017

In a comment on SlateStarCodex today the author (“leoboiko”) advocates a programme of socialism under the assumption that intelligence and ability are inherited, rather than earned, by their possessors. She said,

For one thing, this means that the idea of “meritocracy” is inherently unfair. Giving people access to wealth and resources based on their IQ-related achievements is as unfair as making people richer when they’re born taller. We would want some sort of social program to guarantee everyone access to a decent life according to their needs, not according to their abilities.

And went on to illustrate the unfairness of a world in which wealth was allocated according to height.

I do think intelligence and ability is mostly genetic, and I agree that’s unfair. My response is,

What we are rewarding (and want to reward) is success in helping society progress – materially, culturally, etc. Helping other people. Making the world a better place to live.

Our society is not meritocratic in any sense. We don’t reward merit. Or intelligence. Being meritorious, well-intentioned, hard-working, intelligent, and capable gets you…nothing. What gets rewarded (imperfectly, of course) is actually delivering the result – benefits to other people, as evaluated by those people, by their willingness to voluntarily trade wealth for those benefits.

Intelligence is associated with wealth because we reward pro-social activity, and intelligence makes success in such activity more likely. Height doesn’t (except in basketball).

Steve Jobs wasn’t wealthy because he needed it, or because he was a nice guy (he seems to have been an unpleasant person in many ways). He was wealthy because he created great things that benefited billions of people.

That’s as it should be. It’s not, and never has been, about fairness. It’s about incentives.

Without such incentives, capable people wouldn’t try very hard. And wouldn’t control large amounts of capital for use in their projects. And we all would be far worse off.

Of course I’m not claiming our society does this perfectly or consistently. There are lots of ways to cheat the system, and lots of people who become wealthy in ways other than “making the world a better place” – most obviously, monopolists, tricksters, and power brokers. I advocate fixing that.

But the basic system works. Making the world a better place to live is more important than fairness.

Stupid vs. Evil

November 5th, 2016

It is traditionally held in the United States that there are two major political parties, which can fairly be described as the “Stupid” party and the “Evil” party.

Thoughtful partisans on each side are firmly convinced that their own party is the “Stupid” party, while the opposition is the “Evil” party.

(If you think the situation is less symmetrical than that, I submit that this is an indicator of your partisanship.)

However, this is wrong.

Both parties, like the electorates that support them, and humanity in general, are about 80% stupid and 20% evil.

Proposed anti-political dynasty amendment

November 5th, 2016

A proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States:

No person who is a child, grandchild, sibling, parent, spouse, or former spouse of any present or former President of the United States shall be eligible to the Office of President. This article shall not apply to any person holding the office of President, or acting as President, during the term within which this article becomes operative.

Despite what you may think, this is not motivated by any particular candidate or former President; just something I’ve been meaning to propose for a while.

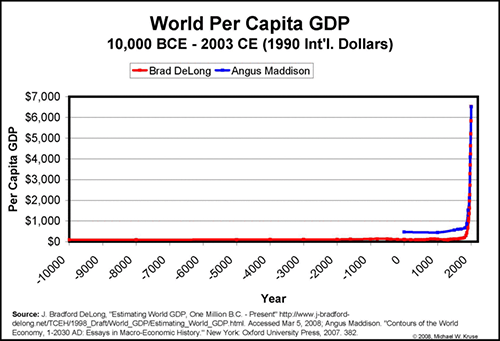

Like many people, I long worried about the specter of technological unemployment – as machines get smarter and gradually can do the jobs that people do, will we reach a point where machines can do everything people can do?

If and when that happens, we may have a paradise of abundance – machines will make everything we want, without any people needing to work.

But at the same time, how will people get money to buy these things?

I no longer think that’s going to be a problem.

Last week’s Economist had an excellent report on “The return of the machinery question”, which examines the problem from a historical perspective. People, after all, have been thinking about this problem since the start of the industrial revolution.

Despite all the hand-wringing, the economy always seems to generate more jobs than automation displaces.

Now I understand why (others have understood for a long time).

I’ll explain with a simplified economic model.

LIMITED STUFF-MAKING ABILITY

At any given time, the world (or national) economy has the ability to produce a certain amount of stuff. Food, clothing, houses, cars, entertainment, etc. – all the things we humans want.

How much stuff we can produce at any given time depends on:

- Labor: How many people exist (each has hands and brain)

- Capital: How many machines, factories, buildings, etc. we’ve accumulated. How much education people have received, etc.

- Resources: How much raw materials we can easily get at – metals, chemicals, energy, land, etc.

- Technology: The ways we know to do things and use the things we have.

Of course how well we use these things matters – we can run factories 24×7 or only 8 hours/day. We can have rules that make us waste time and materials, or incent people to be efficient. We can work long hours, or take lots of vacations.

And over time how much of these things we have changes – population can grow or shrink, resources can be discovered or run out, and we can discover new ways to do things that are better.

But, still, there are limits. At any given time, we can only produce some limited amount of stuff.

LIMITED MONEY

Also at any given time, there is a (again, roughly) fixed amount of money in the world.

Sure, we can print more, but that doesn’t help. If we can make a billion stuffs each day, and there are a billion dollars of money, then the billion dollars will buy all the stuffs, so 1 stuff for each dollar.

(I said this was simplified.)

But if we print another billion dollars, that doesn’t help. Now there are 2 billion dollars, but still only 1 billion stuffs each day. So you need 2 dollars to buy each stuff. (This is inflation.)

MONEY CAN ONLY BE SPENT ON PEOPLE

When someone buys something, they give money to some person.

Yes, you can buy a building, which is not a person. But to buy it, you give money to a person (who owned it).

The same is true with everything – whether you’re buying labor or capital or resources or technology – the money goes to people.

There’s no place else it can go, except to people.

NOW INTRODUCE ROBOTS

So, we can make a given amount of stuff, and the given amount of money will buy that stuff.

And money can only be spent on people.

Now we introduce lots of robots that can do most of the jobs that people do. The robots are cheaper to use than humans, so they get used instead of people.

So now there are people doing nothing, who used to be making stuff.

I just said “the robots are cheaper”. This is key.

Let’s simplify some more and assume we’re still making the same amount of stuff (actually we’ll be making more, which makes things better, but let’s ignore that for now).

So we’re making the same amount of stuff, but the robots are cheaper. That means somebody has extra money left over (probably whoever is using the robots, but that’s not important, as we shall see).

Same amount of stuff. Extra money left over. Which can only be spent on people.

The extra money will eventually get spent (that’s the only thing money is useful for – being spent).

If it’s spent on stuff made by robots, there is still extra money left over. Because robots don’t get paid, only people do.

Yes, robots cost money, but that money is paid to people – the people who make or own them.

So there is still extra money around. Held by people. They can spend it on more robot stuff as much as they like, but that doesn’t use up the money – it just moves it around to other people.

And since we’re already making as much stuff as before, that means it has to be spent on new stuff made by people, that wasn’t being made before. That’s the only place it can be spent.

So now we’re making more stuff than before. And that new stuff was made by people. And the only people available – who aren’t already busy making the old stuff – are the ones who lost their jobs to robots.

So those are the people who get hired to make the new stuff.

That’s it. That’s the whole enchilada.

That’s why despite 200 years of worries, technology has never caused mass unemployment.

Because it can’t. There is only so much money around at a given time. If money is saved by cheaper robots, that money gets spent on people.

(Yes, technology has caused, and will cause in the future, adjustment problems as people switch jobs. That’s different, and while not minor or trivial for the people involved, temporary.)

Finally – Since the robots are cheaper, prices for the stuff they make go down. Which means people can afford to buy more of them.

Which means that people actually get wealthier, in terms of how much stuff they can afford to buy. (They don’t necessarily have more money – they might have more or less – but they can afford more stuff.)

They can’t buy more of the stuff made by people, but they can buy more of the stuff made by robots. Which means stuff made by people is more expensive – more valuable – than stuff made by robots.

Which means the wages of the people who make stuff has gone up, in terms of what the money you pay them will buy.

Up, not down.

Technology makes wages rise. Not decline. Rise.

And that is why we have nice things today, like houses, and medicine, and air conditioning, and clean rivers, and airliners, and indoor toilets, and the Internet, that our ancestors with little technology didn’t have.