I invented many common & important technologies

April 15th, 2013

Did you know I invented many of the key technologies used to drive today’s world?

It’s true – I did. All by myself. I ran across this yesterday:

It’s a 2011 scribble from when I was inventing deconvolution.

In fact I’ve invented so many common technologies that I’ve forgotten about most of them. A few that I do remember are:

| Technology | Concept | Implementation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dither | ~1974 | – | As a child playing with circuits. |

| FIFO queues | 1978 | 1978 | I called them “circular buffers”; never heard of terms “FIFO” or “queue”. |

| Remote Desktop[1] | ~1980 | – | I was going to do it for the TRS-80 (Models I and III) and call it “Guest/Host”. |

| Web prefetch | ~1984 | – | Well, prefetch for web-like services, anyway. Pre-fetch the results from each of the 6 or so menu options on CompuServe Information Service (CIS), to save download time on your 300 bps modem. |

| Key splitting | ~1990 | – | Split a key into N parts, of which M (M <= N) are needed to use the key. |

| Google Earth | 1990 | 1991 | I started a company to do it. We were going to use CD-ROMs, because they hold so much data. Sigh. |

| Internet-controlled thermostat | 1997 | – | From my notes: “Thermostat with Internet interface so you can remotely set and test (and read history?) via Internet (or POTS); for travelers.” |

| Superresolution | ~1999 | – | Motivated by early digicams with lenses that could resolve more detail than the sensors of the time. |

| Deconvolution | ~1999 | 2011 | For lensless imaging. Dropped it when I discovered it required far more bits of ADC than available in real sensors (or even real photons). |

| Camera orientation sensor | ~2001 | – | Gravity sensor in digital camera detects if it’s being held in landscape or portrait orientation, then sets a bit in the image to display it properly. |

Of course, I don’t claim to have been the first to invent any of these things.

The astute reader will note that all these invention dates are all long after these technologies were already well-known. That’s because I re-invented them independently (having never heard of them). The chance to do that is one of the perks of having little formal education.

I’ve often thought that more than 99% of what any individual learns during a lifetime is lost when they die – only the tiny fraction of 1% that gets written down, successfully taught, or copied, benefits anyone else. It’s a terrible waste.

And this shows that even for that tiny fraction of 1% that is written down, many people (perhaps most?) end up having to re-discover it from scratch, either because that’s easier than understanding someone else’s explanation, or because it’s too hard to find out that someone else already has solved the problem.

Makes you think a bit about the meaning of “obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art“, doesn’t it?

[1] I did have a little bit to do with inventing RDP (the first invention, that is), but that wasn’t till the 1990s…

Does Vonage think Republicans are “evil-berries”?

April 10th, 2013

I know “funny machine translation” has been done to death, but I can’t resist:

Date : Apr 06 2013 11:58:21 AM From : unavailable To : Dave “Hi this is Gabriel Gomez call. I wanna(?) to call here-this(?) myself and let you know that I’m running for United States Senate and evil-berry(?) Republican primary. I’m not a politician I’m in the guy is(?) … ceiling(?) pilot and the-supplement-or-rent-i’ve(?) lived the American dream and I know that it must you can’t(?) be preserved. The rid of lack of ideas in Washington the lack of courage. I hope you’ll visit www. Gomez. Ethel r(?) MA.com. To learn about my plan to reboot(?) Congress term limits a balanced budget amendment and i-live-in-the(?) door just a few of the super boring. All five-four(?) I would love to hear from you to discuss your ideas for how to fix Washington. You can e-mail me at Gabriel at Gomez Apple R M a.com or call us at 6173494113. Again your ideas and more about our campaign.”

… more. Please listen to your voicemail for the remainder of this message.— Brought to you by Vonage —

This email was sent from a mailbox that does not accept replies.

If you require assistance from Customer Care, please visit our Contact Us page athttp://www.vonage.com/help_contactUS.php

If you listen to the message, it doesn’t sound as bad as all that. Does Vonage’s transcription engine really think that “evil-berry” is the most likely thing it heard? Maybe.

Perhaps it had to come to this…

December 18th, 2012

From Techdirt, 2012-12-17:

China Tries To Block Encrypted Traffic

from the collapsing-the-tunnels deptDuring the SOPA fight, at one point, we brought up the fact that increases in encryption were going to make most of the bill meaningless and ineffective in the long run, someone closely involved in trying to make SOPA a reality said that this wasn’t a problem because the next bill he was working on is one that would ban encryption. This, of course, was pure bluster and hyperbole from someone who was apparently both unfamiliar with the history of fights over encryption in the US, the value and importance of encryption for all sorts of important internet activities (hello online banking!), as well as the simple fact that “banning” encryption isn’t quite as easy as you might think. Still, for a guide on one attempt, that individual might want to take a look over at China, where VPN usage has become quite common to get around the Great Firewall. In response, it appears that some ISPs are now looking to block traffic that they believe is going through encrypted means.

A number of companies providing “virtual private network” (VPN) services to users in China say the new system is able to “learn, discover and block” the encrypted communications methods used by a number of different VPN systems.

China Unicom, one of the biggest telecoms providers in the country, is now killing connections where a VPN is detected, according to one company with a number of users in China.

This is the culmination of at least 35 years of official concern about the effects of personal computers.

I’m old enough to remember. As soon as computers became affordable to individuals in the late 1970s there was talk about “licensing” computer users. Talking Heads even wrote a song about it (Life During Wartime).

The good guys won, the bad guys lost.

Then, even before the Web, we had the Clipper chip. The EFF was created in response. And again the good guys won.

Then we had the CDA, and then CDA2. And again, the bad guys lost and the lovers of liberty won.

In the West, the war is mostly over (yet eternal vigilance remains the price of liberty).

Not so in the rest of the world, as last week’s ITU conference in Dubai demonstrated.

I say – let them try it. Let them lock down all the VPNs, shut off all the traffic they can’t parse. Let’s have the knock-down, drag-out fight between the hackers and the suits.

Stewart Brand was right. Information wants to be free. I know math. I know about steganography. I know about economics.

I know who will win.

Another airplane window photo

November 29th, 2012

I haven’t been able to find my glory photos, but here is a nice shot out the airplane window of another airliner at the same altitude, with it’s contrail.

(click for full size)

You’re looking south on a flight to Boston from some airport in Europe. Taken 3 December 2005 with a Canon A95 compact camera. Cropped and sharpened a little, that’s all.

Here’s a horribly low-resolution video taken about 5 minutes earlier:

Photos from an airplane window

November 14th, 2012

Back in November 2011 I was flying from San Francisco to Boston, and saw this out the airplane window:

That’s Manhattan and greater New York.

I grabbed my camera (a rather ordinary Canon G11) and started snapping. Here are the best (click on any pic for full size):

These are all un-retouched JPEGs, straight of of the camera. Amazing.

I just made a little animated GIF out of a few later pix:

Questions are more valuable than answers

October 24th, 2012

…at least if you’re Google.

The interesting site Terms of Service; Didn’t Read gives Google a thumbs-down because “Google can use your content for all their existing and future services”.

I don’t think a thumbs-down is really fair here – I mean, that’s the whole point of Google.

Google is a service that gives out free answers in exchange for valuable questions.

Answers are worthless to Google (though not to you) because Google already knows those answers. But it doesn’t know your questions. So the questions are valuable (to Google, not to you). Because Google learns something from every question.

When you start typing a search into Google and it suggests searches based on what other people have searched for, that’s using your private information (your search history) to help other people. They’re not giving away any of your personal information (nobody but Google knows what you searched for or when), but they are using your information.

Google gets lots of useful information from the questions that people ask it. It uses that information to offer valuable services (like search suggestions) to other people (and to you), that they make money from (mostly by selling advertising).

That’s not a bad thing. It’s the only way to do many of the amazing, useful, and free things that Google does. I’m perfectly fine with it, but you have to more-or-less trust Google to stick to their promise to keep your private info private.

I think Google does a lot more of this than most people suspect.

When you’re driving and using Google Map to navigate, you’re getting free maps and directions. But Google is getting real-time data from you about how much traffic is on that road, and how fast it’s moving.

When you search for information on flu symptoms, Google learns something about flu trends in your area.

Sometimes I ask Google a question using voice recognition and it doesn’t understand. After a couple of tries, I type in the query. I’ve just taught Google what I was saying – next time it’s much more likely to understand.

When you use GMail, Google learns about patterns of world commerce and communication, who is connected to who, who is awake at what time of day, etc. Even if it doesn’t read the contents of the mail.

When you search for a product, Google learns about demand in that market, by location and time of day and demographics (it knows a lot about you and your other interests).

Google learns from our questions – answers are the price Google pays for them.

Americans love war

October 21st, 2012

Probably so does the rest of humanity.

Here in the USA, we have:

- The War on Cancer

- The War on Drugs

- The War on Poverty

- The War on Drunk Driving

- Hoover’s “War on Crime”

- Jimmy Carter said the 1970s energy crisis was “the moral equivalent of war”

Then we have the “Good War”, war movies (good guys vs. bad guys), war heroes, and countless war metaphors.

All these wars are supposed to be good things. Necessary things.

Whatever else he was, Jimmy Carter didn’t seem like a nasty guy. But think about “the moral equivalent of war”. Was Carter saying that he thought it was OK to lie in order to deal with the energy crisis? To cheat? Steal? Kill?

Cheating, lying, destruction, theft, and murder are all allowed (indeed, acclaimed) in war.

So is groupism that would otherwise be criminal – in war, when the enemy leaders attack you, it’s OK to respond by killing innocent civilians – so long as they’re subjects of your enemy. Or, even, just in the way.

We declare war on whatever we don’t like because, in war, the normal rules of civilized society don’t apply. And people, especially people in power, don’t like to be constrained by the rules of civilized behavior.

The universe is not parsimonius

October 21st, 2012

One of the defining characteristics of the universe is that it is not parsimonious.

Consider that fish produce many thousands of offspring to replace themselves once – all but two don’t make it to reproduction.

Consider evolution.

Consider the proportion of the Earth’s mass that participates in the biosphere. Of the solar system’s mass. Of the galaxy’s mass.

Consider the number of planets in the universe, and the number that have people on them (~ one).

Consider the proportion of the universe’s mass that is even matter. And the proportion of matter that has an atomic number greater than two.

Now consider the Many Worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics.

The universe is not parsimonious.

[This is not to disparage Occam’s Razor. Parsimony in explanation is indispensable. But the thing being explained need not itself be parsimonious.]

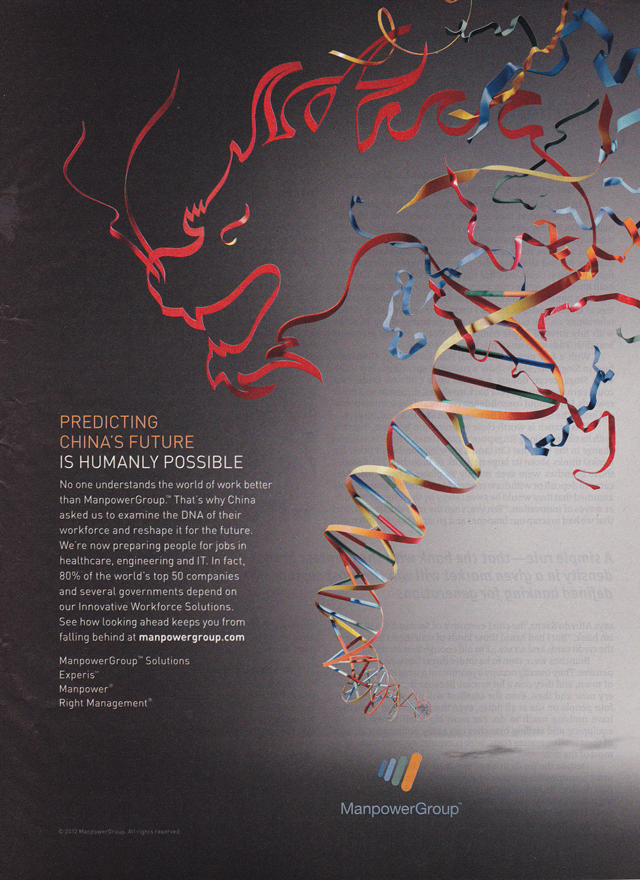

Reshaping DNA

May 30th, 2012

Why school reform never works

March 4th, 2012

Annie Keegan has a posting on open.salon.com about textbook quality that has been getting a lot of attention lately. It’s worth a quick read.

She bemoans the quality of (US) K-8 math textbooks, and blames it on rushed and underfunded development schedules caused by the greed of a quasi-monopoly of “educational publishers left after rabid buyouts and mergers in the 90s”, plus squeezed budgets.

Of course this is true in a trivial sense – the textbooks are in fact horrible, publishers do try to maximize profits, budgets are always less than one would wish, and the textbooks are indeed “there’s no other way to put it—crap”[1].

But she completely misunderstands the causes. And this misunderstanding is likely to lead to more of the same problems, instead of solutions.

Keegan writes:

At one time, a writer in this industry could write a book and receive roughly 6% royalties on sales. The salesperson who sold the product, however, earned (and still does) a commission upwards of 17% on the same product. This sort of pay structure never made sense to me; without the product, there’d be nothing to sell, after all. But this disparity serves to illustrate the thinking that has been entrenched industry-wide for decades—that sales and marketing is more valuable than product.

First, the 6% royalty on all sales of the book is not comparable to the 17% commission on an individual sale to a single school. The salesperson only earns commission on what she sells. There are many salespeople who split that 17% of the book’s total sales, but only one author who collects all of the royalties.

And I don’t think Keegan would complain that a bookshop earning a 40% markup on a book is an indication that retailing is somehow more important than authorship.

Second, the “the thinking that has been entrenched industry-wide” does not decide how “valuable” each contribution to making a book is. There could never be any consensus on that.

Instead, compensation is based on supply and demand – if more people want to be textbook authors, that increases the supply and reduces the pay. If less people want to sell them, that decreases the supply and increases the value of salespeople. If Ms. Keegan thinks salespeople have a better deal, perhaps she should become one – this is how the market shifts labor (and other resources) from less-valuable to more-valuable purposes. If she prefers to remain an author despite the (supposedly) lower pay, that’s her choice, and that choice shows that, to her, being an author (with lower pay) is better than being a book salesperson (with higher pay). She ought not to complain if she is better off — by her own standards.

But none of these misunderstandings get to the heart of why the books are “crap”.

The books are not crap because of the publisher’s greed and the limited budgets.

People who make televisions and plumbing supplies and instant noodles are greedy humans, too. And the people who buy them always wish they had more money to spend than they do. Yet these things aren’t crap.

School textbooks are crap because, unlike televisions and plumbing supplies and instant noodles, the people who make the decision to buy them (administrators and school boards) are not the same people who use them (students and parents).

These two groups of people – buyers and users – have different priorities. The quality of content is foremost for the users of the textbook, but the buyers are easily influenced by other things – fun trips to “educational seminars”, fancy lunches paid by salespeople, kickbacks of varying forms and legality, etc.

In the end, publishers must supply what buyers want, or face being replaced by other publishers who will. What students and parents want is relevant only insofar as it influences what buyers want. Even if a publisher were to have high standards, ensure adequate budgets and schedules, etc. to produce a high-quality product, this would only mean that their expenses would be higher than those of publishers who concentrate only on what sells books.

This problem cannot be solved by changing how publishers work or how school boards and administrators buy textbooks. Buyers will always do what is good for buyers and sellers (publishers) will always do what is good for sellers – increasing budgets simply means they will do more of it. This is an iron law of nature.

The only solution is to make the buyers care more about the wishes of the users – parents and students. As long as students are assigned to schools without choice, administrators have little reason to fear losing students and the funding the comes with them – it’s easy to prioritize (and rationalize) their personal interests as buyers over the interests of users. School choice forces administrators to care about losing dissatisfied students and parents – and so to demand quality textbooks.

Like pushing on a string, changing what suppliers offer does not change what buyers want. Buyers will simply find other suppliers with less scruples. You can only pull on a string – change will happen only when buyers demand better quality from publishers, and that can happen only when buyers and users have the same interest – quality textbooks and quality education.

————-

[1] Of course the whole issue with math textbooks is moot because math doesn’t change; there’s no reason to update math textbooks in the first place. If you’re a school, my advice is to find a good math textbook that’s 100+ years old (and therefore out of copyright) and use it.

But book salespeople won’t take you on fun trips if you do that, so while this advice is best for your students, it might not be best for you as an administrator. Which is my larger point.

(Some will say that math doesn’t change but teaching methods do – I agree, but for the very same reasons that textbooks are “crap”, they don’t change for the better.)