Smile economics – maybe Pope Francis is right

September 22nd, 2013

I read today that Pope Francis thinks the global economic system shouldn’t be based on “a god called money”, and that “Men and women have to be at the centre (of an economic system) as God wants, not money.”

Maybe he’s right. Our economic system should be about people – that’s who it is supposed to be for.

We should have an economic system that encourages people to help each other out, and voluntarily give one another the things they need. One that works without threats and coercion, and which makes people want to be nice and helpful to each other.

Here’s an idea I’ll call “smile economics” – it’s based on an economy of “smiles”:

Each time someone does something nice for a stranger (helps them out, gives them something they need, etc.), that person should give “smiles” in return – to show their appreciation of the nice thing. It might be a lot of “smiles”, or just a few, depending on how big the favor was.

(This would be mostly for use with strangers – people tend to be naturally nice to their friends and relatives.)

The people who accumulate lots of “smiles” would be those who are especially nice and helpful to others. Of course most people want to be perceived as nice, so wanting to have lots of “smiles” would act as a social incentive to encourage everyone to be nice to each other.

Now, when someone really wants a lot of help or something from other people, they could offer a lot of “smiles” for that help. Other people would know that they can really help someone a lot, if that person is offering a lot of “smiles” for the help. Because people want “smiles”, and everyone would know that others wouldn’t offer to give away many “smiles” unless they really wanted the help very much.

Here is the best part – even people who are not naturally nice – selfish people – would want to be nice, in order to get “smiles”.

Why? It’s true that nasty people often don’t care what people think about them. But in order to get help and other things they want from strangers, they’d need to offer “smiles”. Probably they’d have to offer even more “smiles” than nice people, because people don’t generally want to help nasty people. So, in the “smile economy”, nasty people would have to to be nice to others, in order to get the “smiles” they need to get the things they selfishly want for themselves. (Because, in this system, they can’t just buy what they want with money – they need “smiles”.)

“Smile economics” actually makes nasty people want to act nice, in order to satisfy their own selfish desires. It actually makes their own selfish interest drive them to be nice to other people! How about that!?

Of course, to do the most good, the system should be utterly universal and work between strangers of all races, religions, and nations, no matter where they are. We want to encourage people to be nice to one another no matter who they are. Anyone who said, for example, that someone in Brazil shouldn’t do nice things for someone in China (or any other pair of countries) would be seen as evil – because wanting people not to be nice to each other is evil. Nobody should ever tell anyone not to be nice to one another.

What do you think?

Addendum – A few people who have read this think it won’t work because people can just make fake “smiles” all the the time (as many as they want) in order to get things. They have a point. So let’s say that everybody gets a certain limited number of “smiles” to spend – maybe eight or ten each day (they can save them as long as they like).

Addendum #2 – In case it still isn’t clear, it doesn’t need to be “smiles” that people give as a reward. It could be anything that’s limited in number which other people value – for example pretty marbles (if they’re hard to get), or shiny rocks, or little pieces of gold. Or what the Spanish used to call “pesos de ocho” (pieces of eight). Or Greek drachma, Pakistani rupees, or Thai baht. Japanese Yen would work. Or Bitcoins. I suppose those all have their pros and cons, but it doesn’t really matter.

You get the idea now, I’m sure. Pope Francis is going to love this idea!!

I invented many common & important technologies

April 15th, 2013

Did you know I invented many of the key technologies used to drive today’s world?

It’s true – I did. All by myself. I ran across this yesterday:

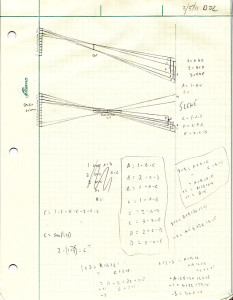

It’s a 2011 scribble from when I was inventing deconvolution.

In fact I’ve invented so many common technologies that I’ve forgotten about most of them. A few that I do remember are:

| Technology | Concept | Implementation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dither | ~1974 | – | As a child playing with circuits. |

| FIFO queues | 1978 | 1978 | I called them “circular buffers”; never heard of terms “FIFO” or “queue”. |

| Remote Desktop[1] | ~1980 | – | I was going to do it for the TRS-80 (Models I and III) and call it “Guest/Host”. |

| Web prefetch | ~1984 | – | Well, prefetch for web-like services, anyway. Pre-fetch the results from each of the 6 or so menu options on CompuServe Information Service (CIS), to save download time on your 300 bps modem. |

| Key splitting | ~1990 | – | Split a key into N parts, of which M (M <= N) are needed to use the key. |

| Google Earth | 1990 | 1991 | I started a company to do it. We were going to use CD-ROMs, because they hold so much data. Sigh. |

| Internet-controlled thermostat | 1997 | – | From my notes: “Thermostat with Internet interface so you can remotely set and test (and read history?) via Internet (or POTS); for travelers.” |

| Superresolution | ~1999 | – | Motivated by early digicams with lenses that could resolve more detail than the sensors of the time. |

| Deconvolution | ~1999 | 2011 | For lensless imaging. Dropped it when I discovered it required far more bits of ADC than available in real sensors (or even real photons). |

| Camera orientation sensor | ~2001 | – | Gravity sensor in digital camera detects if it’s being held in landscape or portrait orientation, then sets a bit in the image to display it properly. |

Of course, I don’t claim to have been the first to invent any of these things.

The astute reader will note that all these invention dates are all long after these technologies were already well-known. That’s because I re-invented them independently (having never heard of them). The chance to do that is one of the perks of having little formal education.

I’ve often thought that more than 99% of what any individual learns during a lifetime is lost when they die – only the tiny fraction of 1% that gets written down, successfully taught, or copied, benefits anyone else. It’s a terrible waste.

And this shows that even for that tiny fraction of 1% that is written down, many people (perhaps most?) end up having to re-discover it from scratch, either because that’s easier than understanding someone else’s explanation, or because it’s too hard to find out that someone else already has solved the problem.

Makes you think a bit about the meaning of “obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art“, doesn’t it?

[1] I did have a little bit to do with inventing RDP (the first invention, that is), but that wasn’t till the 1990s…

Perhaps it had to come to this…

December 18th, 2012

From Techdirt, 2012-12-17:

China Tries To Block Encrypted Traffic

from the collapsing-the-tunnels deptDuring the SOPA fight, at one point, we brought up the fact that increases in encryption were going to make most of the bill meaningless and ineffective in the long run, someone closely involved in trying to make SOPA a reality said that this wasn’t a problem because the next bill he was working on is one that would ban encryption. This, of course, was pure bluster and hyperbole from someone who was apparently both unfamiliar with the history of fights over encryption in the US, the value and importance of encryption for all sorts of important internet activities (hello online banking!), as well as the simple fact that “banning” encryption isn’t quite as easy as you might think. Still, for a guide on one attempt, that individual might want to take a look over at China, where VPN usage has become quite common to get around the Great Firewall. In response, it appears that some ISPs are now looking to block traffic that they believe is going through encrypted means.

A number of companies providing “virtual private network” (VPN) services to users in China say the new system is able to “learn, discover and block” the encrypted communications methods used by a number of different VPN systems.

China Unicom, one of the biggest telecoms providers in the country, is now killing connections where a VPN is detected, according to one company with a number of users in China.

This is the culmination of at least 35 years of official concern about the effects of personal computers.

I’m old enough to remember. As soon as computers became affordable to individuals in the late 1970s there was talk about “licensing” computer users. Talking Heads even wrote a song about it (Life During Wartime).

The good guys won, the bad guys lost.

Then, even before the Web, we had the Clipper chip. The EFF was created in response. And again the good guys won.

Then we had the CDA, and then CDA2. And again, the bad guys lost and the lovers of liberty won.

In the West, the war is mostly over (yet eternal vigilance remains the price of liberty).

Not so in the rest of the world, as last week’s ITU conference in Dubai demonstrated.

I say – let them try it. Let them lock down all the VPNs, shut off all the traffic they can’t parse. Let’s have the knock-down, drag-out fight between the hackers and the suits.

Stewart Brand was right. Information wants to be free. I know math. I know about steganography. I know about economics.

I know who will win.

Reshaping DNA

May 30th, 2012

Why school reform never works

March 4th, 2012

Annie Keegan has a posting on open.salon.com about textbook quality that has been getting a lot of attention lately. It’s worth a quick read.

She bemoans the quality of (US) K-8 math textbooks, and blames it on rushed and underfunded development schedules caused by the greed of a quasi-monopoly of “educational publishers left after rabid buyouts and mergers in the 90s”, plus squeezed budgets.

Of course this is true in a trivial sense – the textbooks are in fact horrible, publishers do try to maximize profits, budgets are always less than one would wish, and the textbooks are indeed “there’s no other way to put it—crap”[1].

But she completely misunderstands the causes. And this misunderstanding is likely to lead to more of the same problems, instead of solutions.

Keegan writes:

At one time, a writer in this industry could write a book and receive roughly 6% royalties on sales. The salesperson who sold the product, however, earned (and still does) a commission upwards of 17% on the same product. This sort of pay structure never made sense to me; without the product, there’d be nothing to sell, after all. But this disparity serves to illustrate the thinking that has been entrenched industry-wide for decades—that sales and marketing is more valuable than product.

First, the 6% royalty on all sales of the book is not comparable to the 17% commission on an individual sale to a single school. The salesperson only earns commission on what she sells. There are many salespeople who split that 17% of the book’s total sales, but only one author who collects all of the royalties.

And I don’t think Keegan would complain that a bookshop earning a 40% markup on a book is an indication that retailing is somehow more important than authorship.

Second, the “the thinking that has been entrenched industry-wide” does not decide how “valuable” each contribution to making a book is. There could never be any consensus on that.

Instead, compensation is based on supply and demand – if more people want to be textbook authors, that increases the supply and reduces the pay. If less people want to sell them, that decreases the supply and increases the value of salespeople. If Ms. Keegan thinks salespeople have a better deal, perhaps she should become one – this is how the market shifts labor (and other resources) from less-valuable to more-valuable purposes. If she prefers to remain an author despite the (supposedly) lower pay, that’s her choice, and that choice shows that, to her, being an author (with lower pay) is better than being a book salesperson (with higher pay). She ought not to complain if she is better off — by her own standards.

But none of these misunderstandings get to the heart of why the books are “crap”.

The books are not crap because of the publisher’s greed and the limited budgets.

People who make televisions and plumbing supplies and instant noodles are greedy humans, too. And the people who buy them always wish they had more money to spend than they do. Yet these things aren’t crap.

School textbooks are crap because, unlike televisions and plumbing supplies and instant noodles, the people who make the decision to buy them (administrators and school boards) are not the same people who use them (students and parents).

These two groups of people – buyers and users – have different priorities. The quality of content is foremost for the users of the textbook, but the buyers are easily influenced by other things – fun trips to “educational seminars”, fancy lunches paid by salespeople, kickbacks of varying forms and legality, etc.

In the end, publishers must supply what buyers want, or face being replaced by other publishers who will. What students and parents want is relevant only insofar as it influences what buyers want. Even if a publisher were to have high standards, ensure adequate budgets and schedules, etc. to produce a high-quality product, this would only mean that their expenses would be higher than those of publishers who concentrate only on what sells books.

This problem cannot be solved by changing how publishers work or how school boards and administrators buy textbooks. Buyers will always do what is good for buyers and sellers (publishers) will always do what is good for sellers – increasing budgets simply means they will do more of it. This is an iron law of nature.

The only solution is to make the buyers care more about the wishes of the users – parents and students. As long as students are assigned to schools without choice, administrators have little reason to fear losing students and the funding the comes with them – it’s easy to prioritize (and rationalize) their personal interests as buyers over the interests of users. School choice forces administrators to care about losing dissatisfied students and parents – and so to demand quality textbooks.

Like pushing on a string, changing what suppliers offer does not change what buyers want. Buyers will simply find other suppliers with less scruples. You can only pull on a string – change will happen only when buyers demand better quality from publishers, and that can happen only when buyers and users have the same interest – quality textbooks and quality education.

————-

[1] Of course the whole issue with math textbooks is moot because math doesn’t change; there’s no reason to update math textbooks in the first place. If you’re a school, my advice is to find a good math textbook that’s 100+ years old (and therefore out of copyright) and use it.

But book salespeople won’t take you on fun trips if you do that, so while this advice is best for your students, it might not be best for you as an administrator. Which is my larger point.

(Some will say that math doesn’t change but teaching methods do – I agree, but for the very same reasons that textbooks are “crap”, they don’t change for the better.)

Copying is not theft

February 24th, 2011

Another letter to the Economist:

Date: Thu, 24 Feb 2011 09:06:36 -0600

To: letters [at] economist.com

From: Dave <dave [at] mugwumpery.com>Subject: Re “Ending the open season on artists”, 19 February

Dear Sir,

As a an “aghast” digital libertarian, I object to your presumption that stronger copyright enforcement is good or necessary for artists.

No one disputes that artists must be rewarded for successful creation. (Middlemen are another story.) Copyright was a reasonably effective system when copying was expensive anyway and the means of reproduction were relatively centralized publishers and distributors, easily policed. Now that works can be copied costlessly by any individual, the principle of limiting copying is both unworkable and inappropriate, as copying (although illegal) is not theft – because copying does not deprive the original owner of anything.

Certainly, artists must eat. The challenge is to find new business and legal models to accomplish that without needlessly depriving the public of the full enjoyment of the fruits of creation.

Attempts to perpetuate obsolete business models by law are not the solution.

It is hard to make a strong argument in a letter short enough to get published.

My larger point is that there is what economists call a “deadweight loss” when someone who would have enjoyed a creative work doesn’t because of costs imposed by copyright.

Say we’re talking about a copy of The Beatles “A Hard Day’s Night” (which, completely off-topic, has some of the lamest lyrics imaginable – “…to get you money to buy you things“??).

Some consumers are willing to pay the asking price for the song under the copyright system. In that case the artists get 10 or 20%, and the middlemen get the rest. (And yes, the studio technicians, etc. need to get paid too, but not necessarily by a record company – painters seem quite able to buy blank canvas without middlemen to help.)

But more consumers (usually far more) are not willing to pay that much. They’d enjoy having a copy of the song, but not enough to justify the price. These people are going to be in the majority almost regardless of the price asked. This is the deadweight loss; value that could have been realized without cost to anyone, but wasn’t.

To make it clearer – imagine we’re talking about a $1000 copy of Adobe Photoshop instead. How many of the people who would benefit from using it are willing to pay that much? Very few. Yet it would cost Adobe nothing at all to let them use it for free – if that didn’t discourage those few who would pay from doing so.

Of course, under the copyright system this loss is necessary to make the system work – otherwise no one at all would pay. And this is precicely the problem with the copyright system – it necessitates the deadweight loss to work.

As I implied in the letter, this wasn’t such a terrible flaw when copying was expensive anyway. Records couldn’t be produced for free; paying the artist a royalty only increased the price a little bit, so not much harm was done. But that’s not true in a world where copying is free.

So we need a new system to reward creators for successful creation that other people value. I can imagine a half-dozen ways to do it; so can you. It will take some experimentation and evolution to get there, but propping up the obsolete copyright system is not going make it come sooner.

The Toyota Witch Trials

March 10th, 2010

No one else seems to be saying it, so I will.

The hysteria about run-away Toyotas is driven by a xenophobic witch hunt.

There is nothing wrong with Toyota vehicles. They do not accelerate uncontrollably. Ever. There’s nothing wrong with the floor mats, electronics, etc. Claims to the contrary are lies.

I’m not going to focus on the engineering reasons why such claims are utterly unbelievable – the chance that the accelerator, brake, gearshift, and ignition all fail simultaneously in a way that allows acceleration and nothing else, then miraculously correct themselves afterward so that there is no sign of any flaw – is as close to zero as anything gets in this world.

It is interesting that Toyota is having these “problems” only in the United States. Not in Japan, China, or Thailand. Not in Australia or New Zealand. Not in the UK, not in Sweden, not in Spain, Germany, Russia, or Romania. Not in Nigeria, South Africa, Botswana, Uganda. Not in Canada. Just in the USA. Even though they sell the same cars in all these places.

And that all the publicity about deadly flaws in Toyota vehicles started in 2009, just after headlines like these:

Toyota Passes General Motors As World’s Largest Carmaker (Washington Post, January 21, 2009)

Toyota Ahead of G.M. in 2008 Sales (New York Times, January 22, 2009)

Toyota now the largest motor-car manufacturer of the world (BusinessWeek, April 11 2009)

I know what you’re thinking. Surely all the claims of malfunctioning cars, actual crashes, etc. can’t be simply made up by jingoistic Americans annoyed that the national champion has been bested by the yellow devils.

No. That’s not what I’m claiming.

There are something like 300 million cars in the USA. If each one is driven once a day, that’s 110 billion trips each year.

When a driver starts a car, there is some small but finite chance she’ll step on the gas by mistake when aiming for the brake. It’s happened to me, and to most people I’ve asked. Most of the time we notice and think “oops – wrong pedal”, and that’s the end of it.

But sometimes, rarely, people don’t notice. Instead they panic. They press harder on the gas, instead of pressing on the brake. They think they’re already pressing on the brake, and the car is going too fast. So they press harder. On the gas.

This doesn’t happen very often. But 110 billion trips/year. Maybe 20% of them in Toyotas. It does happen sometimes.

If the driver is on a highway, usually even if this happens the driver will think to turn off the ignition. Or put the car in neutral. But not always. Some people are just panicky and don’t think clearly in emergencies. Some are bad drivers. And even good drivers can have a bad day.

Eventually, one of two things happens – the car hits something or the driver figures out what happened and lets go of the gas. If there is a crash, the driver may very well believe afterward, in all honesty, that there was something wrong with the car. If there wasn’t an accident, the driver may have made a fool of themselves, caused someone else to have an accident, or got caught speeding. Most people are honest, and will admit they made a simple mistake. But 110 billion trips/year. Not everyone is honest.

This is exactly what happened with Audi in the early 1980s – a few reports made the media and confused or dishonest people suddenly had an excuse to blame someone else for their accidents. Or to sue for damages. There was nothing wrong with Audi’s cars, other than having the gas and brake pedals a little closer together than some drivers were used to. But sensation and terror sells advertising, and most people are stupid enough to believe everything they see in the media.

So – a few Toyota drivers make this kind of mistake, and blame it on the car (mostly in honest confusion). Happens all the time, to all makes and models of car.

But – Toyota Passes General Motors As World’s Largest Carmaker !! For the first time in 77 years!

Some in the media, and many in politics, are carrying a chip on the shoulder – America’s champion has been shamed and defeated by the hated Asian devils! So these claims are not ignored. They’re hyped. Toyota is killing people – their cars are deathtraps! Congressmen demand NHTSA investigations. Soon the CEO of Toyota is committing rhetorical hara-kiri in front of Congress and the TV cameras.

Of course, floor mats can get stuck. So can accelerator pedals. It happens to every make and model. But Toyota’s patient explanation that there is no problem doesn’t work. Reason never works when you’re in a witch hunt. So to protect their reputation and avoid even more expensive punishment, Toyota reluctantly negotiates a recall to glue down floor mats and grease accelerator pedals. Under duress – a sort of plea-bargain with the American government (which is unlikely to honor its end of the deal).

The technical term for the whole thing is bullshit.

[In the interest of full disclosure: I am a shareholder of Toyota Motor Corp. Also of Daimler AG and Honda Motor Co., both of which stand to gain sales from this garbage. As well, I own, among other vehicles, a Toyota Prius. Which I am not going to drag to the dealership for a shamanistic rain-dance to make the evil unintended-acceleration spirits go away.]

Flying Angel Babies – With Weapons

February 14th, 2010

February 14, and again we are afflicted with a swarm of these hallucinogenic creatures.

Obviously LSD wasn’t the first psychedelic.

Power laws

December 19th, 2009

There’s a story on Slashdot today about “a complicated pattern that has to do with the way humans do violence in some collective way“.

Surprise. The size and frequency of terrorist attacks follows a power law – lots of little attacks, a few big ones.

What doesn’t? Quoting from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pareto_distribution:

The sizes of human settlements (few cities, many hamlets/villages) File size distribution of Internet traffic which uses the TCP protocol (many smaller files, few larger ones) Clusters of Bose-Einstein condensate near absolute zero The values of oil reserves in oil fields (a few large fields, many small fields) The length distribution in jobs assigned supercomputers (a few large ones, many small ones) The standardized price returns on individual stocks Sizes of sand particles Sizes of meteorites Numbers of species per genus (There is subjectivity involved: The tendency to divide a genus into two or more increases with the number of species in it) Areas burnt in forest fires Severity of large casualty losses for certain lines of business such as general liability, commercial auto, and workers compensation.

I could add a bunch more, but won’t bother.

Why is this considered news? Why does it get published in Nature? If terrorist activity didn’t follow a power law, I think that would be interesting enough to merit publication in a prestigious journal. But this?

Is it just me, or is the quality of editorial work in science journals dropping? I constantly see papers in Science and Nature that make the most basic scientific mistake possible – confusing correlation with causality. And then the “quality” press such as the New York Times and the Economist pick it up and repeat the same nonsense.

See also:

THINK before you demand authentication

December 2nd, 2008

Today I got an email from Buy.com asking me to review a cell phone battery I’d bought.

Happy with the battery, and feeling like procrastinating for a few minutes, I decided to do it.

I clicked on the link in the email. Buy.com immediately asked for my email address and password.

Now, which of my 5 different emails did I use for that purchase? I guessed – wrong, apparently.

So, forget it. I was going to do them a favor, but now I’m not.

Why do I have to authenticate myself to review a product I bought? They know I bought it. They know who I am – they sent me the email. So why ask again for authentication? They should have included a unique ID in the link, allowing me to write one (1) review for that one product.

Either some idiot at Buy.com thinks it’s necessary to re-authenticate me (likely following some corporate rule set down by God) or they’re just too lazy to bother to think about the situation.

This kind of corporate incompetence is all too common.